Lenin, Trotsky and Stalin - Three Revolutionaries, Three Wise Men or

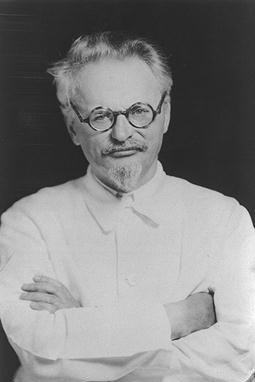

Three Stooges? Let us start with one of the more popular among them

- Leon Trotsky. This is an old article by a British socialist but it

is still valid as it was years ago. Maybe it was even valid when

Trotsky was leading the Red Army in the 1920s.

trotsky: the

prophet debunked

Nearly 60 years ago this month Leon Trotsky was assassinated by an

agent of Stalin's secret police. We take this opportunity to

critically assess his life and views.

Nearly 60 years ago this month Leon Trotsky was assassinated by an

agent of Stalin's secret police. We take this opportunity to

critically assess his life and views.

Trotsky was born Lev Davidovitch Bronstein, the son of moderately

well-off peasant farmers in the southern Ukraine, in 1879.

As a student at the University of Odessa he became an anti-Tsarist

revolutionary. He soon fell foul of the authorities and was

sentenced to prison and exile in Siberia from where he escaped in

1902 using the name of one of his jailers on his false identity

card; this name Trotsky he was to use for the rest of his life.

Trotsky played a prominent part in the 1905 revolt that followed

Russia's defeat in the Russo-Japanese War, being elected the

Chairman of the St. Petersburg "soviet" ("soviet" is simply the

Russian word for "council").

Oddly in view of his later political evolution, when the split

occurred in the Russian Social Democratic movement in 1903 between

the Mensheviks (orthodox Social Democrats like Kautsky in Germany)

and the Bolsheviks (supporters of Lenin and his concept of a

vanguard party of professional revolutionaries), Trotsky tended

to favour the Mensheviks.

Stalin and his supporters later took great pleasure in publishing

one of Trotsky's writings from this period in which he violently

criticised Lenin's conception of the party. Trotsky in fact tried

to develop a middle position, evolving his own theory of how the

anti-Tsarist revolution would develop.

Both the Mensheviks and the Bolsheviks saw the anti-Tsarist

revolution as being one that would lead to the establishment

of a bourgeois Democratic Republic in Russia (the difference

between them was that the Mensheviks tended to see this as

being done by the liberal bourgeoisie while the Bolsheviks

said it would have to be the work of the vanguard party).

Trotsky took up a different position, arguing that if the working

class were to come to power in the course of the coming bourgeois

revolution in Russia it was unreasonable to expect them to hand

over power to the bourgeoisie; they would, and should according to

Trotsky, take steps to transform society in a socialist direction.

Anti-Tsarist revolutionary

This theory, which Trotsky called "the theory of the permanent revolution",

latching on to a phrase used by Marx in one of his articles on the

abortive German bourgeois revolution of 1848-9, was absurd in that

it implied that socialism could be on the agenda in economically backward

Russia. It was however important historically as it was adopted by Lenin

himself in April 1917 when he returned to Russia from exile in Switzerland.

As a result Trotsky himself then rallied to the Bolsheviks.

In a very real sense Bolshevik ideology can be seen as a combination

of Trotsky's theory of the revolution and Lenin's theory of the party.

In 1932 Trotsky wrote a book called The History of the Russian

Revolution, which is essential reading for anyone wanting to

understand this event, not only because the author was an active

participant in it but also because it unintentionally shows how

this wasn't a working class socialist revolution but an anti-feudal

revolution led by a vanguard party.

After the Bolshevik seizure of power Trotsky became, first, Commissar

for Foreign Affairs and, then, Commander of the Red Army which

successfully won the Civil War against the "White Guards" supported

by the Western powers.

This gave him an immense prestige both in Russia and among sympathisers

with the Russian revolution in the rest of the world. His attitude on

other issues during this period was even more anti-working class than

that of Lenin who, on one occasion, was forced to intervene to attack

as going too far Trotsky's proposal to "militarise" labour and the

trade unions.

After Lenin's death Trotsky was gradually eased out of power. He was

exiled first to Alma Ata in Russian central Asia and then to Turkey,

Norway and finally Mexico. If he had stayed in Russia he would almost

certainly have been tortured, tried and shot like Zinoviev, Kamenev,

Bukharin and the other original leaders of the Bolshevik Party. All

the same he still ended up with a Stalinist ice-pick in his head.

Degenerate Workers State

In exile Trotsky played the role of "loyal opposition" to the Stalin

regime in Russia. He was very critical of the political aspects of

this regime (at least some of them, since he too stood for a

one-party dictatorship in Russia), but to his dying day defended

the view that the Russian revolution had established a "Workers State"

in Russia (whatever that might be) and that this represented a gain

for the working class both of Russia and of the whole world.

His view that Russia under Stalin was a Workers State, not a perfect

one, certainly, but a Workers State nevertheless, was set out in his

book The Revolution Betrayed first published in 1936. This is the

origin of the Trotskyist dogma that Russia is a "degenerate Workers

State" in which a bureaucracy had usurped political power from the

working class but without changing the social basis (nationalisation

and planning).

This view is so absurd as to be hardly worth considering seriously:

how could the adjective "workers" be applied to a regime where

workers could be sent to a labour camp for turning up late for work

and shot for going on strike? Trotsky was only able to sustain his

point of view by making the completely unmarxist assumption that

capitalist distribution relations (the privileges of the Stalinist

bureaucracy) could exist on the basis of socialist production

relations.

Marx, by contrast, had concluded, from a study of past and present

societies, that the mode of distribution was entirely determined by

the mode of production. Thus the existence of privileged distribution

relations in Russia should itself have been sufficient proof that

Russia had nothing to do with socialism.

Trotsky rejected the view that Russia was state capitalist on the

flimsiest of grounds: the absence of a private capitalist class, of

private shareholders and bondholders who could inherit and bequeath

their property.

He failed to see that what made Russia capitalist was the existence

there of wage-labour and capital accumulation not the nature and mode

of recruitment of its ruling class.

Trotsky's view that Russia under Stalin was still some sort of "Workers

State" was so absurd that it soon aroused criticism within the ranks of

the Trotskyist movement itself which, since 1938, had been organised as

the Fourth International.

Two alternative views emerged. One was that Russia was neither capitalist

nor a Workers State but some new kind of exploiting class society. The

other was that Russia was state capitalist.

The most easily accessible example of the first view is James Burnham's

The Managerial Revolution and of the second Tony Cliff's Russia: A

Marxist Analysis.

Both books are well worth reading, though in fact neither Burnham nor

Cliff could claim to be the originators of the theories they put forward.

The majority of Trotskyists, however, remain committed to the dogma that

Russia is a "degenerate Workers State".

Transitional Demands

Trotskyist theory and practice is rather neatly summed up in the opening

sentence of the manifesto the Fourth International adopted at its

foundation in 1938. Called The Death Agony of Capitalism and the Tasks

of the Fourth International, and drafted by Trotsky himself, it began

with the absurd declaration: "The world political situation is chiefly

characterised by historical crisis of the leadership of the proletariat".

This tendency to reduce everything to a question of the right leadership

(Trotsky once wrote a pamphlet on the Paris Commune in which he explained

its failure by the absence of a Bolshevik Party there) reminds us that

Trotskyists are 102 per cent Leninists and believers in the vanguard party.

They believe, in other words, that workers by their own efforts are

incapable of emancipating themselves and so must be led by an enlightened

minority of professional revolutionaries (generally bourgeois intellectuals

like Lenin and Trotsky).

Thus they fall under the general criticism of Leninism and indeed of

all theories which proclaim that workers need leaders.

The other important point in the manifesto of the Fourth International

was the concept of "transitional demands". The manifesto contained a

whole list of reform demands which was called "the transitional programme".

This reform programme was said to be different from those of openly reformist

parties like Labour in Britain and the Social Democratic parties on the

Continent in that Trotskyists claimed to be under no illusion that the reforms

demanded could be achieved within the framework of capitalism. They were posed

as bait by the vanguard party to get workers to struggle for them, on the

theory that the workers would learn in the course of the struggle that

these demands could not be achieved within capitalism and so would come to

struggle (under the leadership of the vanguard party) to abolish capitalism.

Actually, most Trotskyists are not as cynical as they pretend to be here: in

discussion with them you gain the clear impression that they share the

illusion that the reforms they advocate can be achieved under capitalism

(as, indeed, some of them could be). In other words, they are often the

victims of their own "tactics".

Splits and sects

After the Second World War, all the Trotskyists in Britain were united

for a time in a single organisation, the Revolutionary Communist Party,

which was affiliated to the Fourth International. All the leaders of the

various Trotskyist sects (Gerry Healy, Ted Grant, Tony Cliff, etc.) were

together in the RCP.

Most of the splits that subsequently occurred were over the attitude to

adopt towards Russia and the Cold War. The group around Cliff, as we

have already noted, took the view that Russia had been state capitalist

since about 1928 (up till then it had supposedly been a "Workers State").

Logically they adopted the slogan "Neither Washington nor Moscow". Longtime

known as the "International Socialists" they are now the Socialist Workers

Party. Except on Russia they share all the other Trotskyist illusions

(vanguard party, transitional demands, etc.).

In 1949 the RCP dissolved itself and most Trotskyists decided to join the

Labour Party and "to bore from within". This tactic, known in Trotskyist

parlance, as "entryism", is again based on the premise that the mass of

the workers need leaders and are there to be manipulated.

As would-be leaders of the working class, the argument goes, we must be

where the workers are; as in Britain the Labour Party is "the mass party

of the working class" this is where we Trotskyists must be if we are to

have a chance of influencing (that is, manipulating) the workers.

After the general strike in France in May 1968, which seemed to show

that student activists could influence the working class directly without

needing to pass through "the mass party of the working class", most of the

Trotskyist groups decided to abandon entryism and openly form their own

parties.

Thus parliamentary elections in Britain came to be enlivened by the

presence of parties bearing such titles as "Workers Revolutionary Party",

"Socialist Workers Party", "Revolutionary Communist Party", "Socialist

Unity", etc. Needless to say, they got no more votes than we in the

Socialist Party did.

This abandoning of entryism should not be interpreted as meaning opposition

to the Labour Party, because nearly all the Trotskyist groups continue

to support the election of a Labour government and to call on workers to

vote Labour.

One Trotskyist sect, however, decided not to abandon the Labour Party after

1968 but to continue boring from within: the sect now known as the

Militant Tendency (leader: Ted Grant). The absence of the other sects meant

that they had a monopoly of this particular hunting ground.

So when Labour turned left after 1979 they were there ready to recruit new

members and increase their influence. In fact the Militant Tendency has

undoubtedly been the most successful of all the Trotskyist groups that have

ever infiltrated the Labour Party.They control a number of constituency

parties as well as the Labour Party Young Socialists.

There are even two or three Trotskyist MP's sitting on the Labour benches

at Westminster.

From an ideological point of view, the Militant Tendency follows orthodox

Trotskyism. Thus, for instance, they regard Russia as a "degenerate

Workers State" which means they are more backward than many Labour Party

members who willingly recognise that Russia is state capitalist.

Trotsky entirely identified capitalism with private capitalism and so

concluded that society would cease to be capitalist once the private

capitalist class had been expropriated.

This meant that, in contrast to Lenin who mistakenly saw state capitalism as

a necessary step towards socialism, Trotsky committed the different mistake

of seeing state capitalism as the negation of capitalism. Trotskyism, the

movement he gave rise to, is a blend of Leninism and Reformism, committed on

paper to replacing private capitalism with state capitalism through a violent

insurrection led by a vanguard party, but in practice working to achieve

state capitalism through reforms to be enacted by Labour governments.